I am concerned about the US economy.

For the first time in decades, there are new structural forces at play that are having a profound impact on the economic landscape, both in the US and, outside of it: from industrial policy like the Inflation Reduction Act to high interest rates to new tariffs on trade, the ground is shifting under the US economy, and it is fundamentally changing the way that actors in the economy interact. It’s a new era, one where the economy is becoming increasingly constrained and directed by broader geopolitical forces.

Unfortunately, the brave new world constructed by geopolitical tensions is not especially friendly to the average American, despite vociferous proclamations to the contrary - something that voters are very clearly noticing. The recent trend toward autarky in the US is interacting negatively with the environment of high inflation and the Federal Reserve’s increased interest rates. Despite high growth, a recession in the US is not out of the question.

To be slightly less cryptic about The Imminent Doom: it’s about demand. Consumers are caught between the anvil of inflation and the hammer of interest rates, and now that all stimulus-related savings have been exhausted, there is nothing left to cushion the blow.

And the last refuge of the consumer before catastrophe is debt.

With that in mind, let’s look at some of the pressures on the US consumer. Put on your oxygen mask, dear reader: we’ll be spelunking for details, starting with an examination of two of the main types of household debt.

Mortgages

Mortgages continue to represent the majority of the debt burden for US households. They are not immune to Federal Reserve action: in fact, mortgage rates are currently at a two-month high. But by and large, mortgages represent a hedge against the burden of interest rates for households. Why? Two reasons.

The first is that the most popular type of mortgage in the US is the 30 year fixed rate mortgage. As the name implies, this means that interest is fixed and is thus immune to shifting interest rates - Federal Reserve action will thus only impact new fixed-rate mortgages, leaving most mortgage holders secure with their responsibly stable debt burden. The 30-year fixed rate has been a staple since its introduction but, more importantly, has become overwhelmingly dominant since 2008 - for understandable reasons. Adjustable-rate mortgages only represent less than 10% of new mortgages.

The stability of the fixed-rate interests also has an impact on the overall housing sector. The US is a rare outlier in that the housing market is remarkably stable when other OECD countries have watched their markets wilt in the face of incredibly high interest rates. House prices are currently at all-time highs despite a drop in demand from entry buyers, at least partially because real estate has become a valuable market for private equity firms - thus neatly sidestepping a need for affordability and taking another step towards houses becoming a speculative asset. Which has never gone wrong before, ever.

This leads us to the second reason. With housing prices so high due to investors, and mortgage rates high because of Federal Reserve action, most Americans can’t afford to rent, much less buy a home. To demonstrate the impact of this crisis of affordability on new mortgages:

This neatly solves the housing market problem: the market can’t crash if demand remains strong due to private equity, and households won’t be crippled by rising interest rates if they only hold fixed-rate debt from 20 years ago when houses were affordable. Mortgage rates are rising, but their impact on the overall consumer remains minimal given the anemic market for fresh debt of this type.

The real question with regards to mortgages is whether these circumstances can last. Leaving to the side for a moment the ethics of a housing crisis largely fueled by the speculative acquisition of assets by private equity, there is the question of whether or not prices can remain at current rates with the broader base for demand this low. Given that the Federal Reserve is expected to drop interest rates sometime this year, there is an expectation that the subsequent impact on mortgage rates will spur greater consumption. But again, this is entirely contingent on all else being equal when interest rates fall - namely, that consumer spending retains its current luster. And there is certainly reason to believe that it will not.

Credit Card Debt

For a long time now, mortgages have been the most significant cornerstone of American debt. But this is currently changing. Credit card debt is fast becoming one of the most significant forms of debt held by US households. This isn’t because of scale - the base amount is dwarfed by mortgage debt - but because of scalability.

Both mortgage debt and credit card debt compound. However, there is a substantial difference between compound interest on a historically high 7% rate and compound interest on a historically high 20% rate, especially for a type of debt that households regularly carry on from month to month. Even a reasonable amount of credit card debt, if left to fester, can become utterly unmanageable in a matter of months.

Another point is the increasing reliance of households on credit cards. With half of Americans reliant on credit for basic monthly necessities, and many of them unable to pay this debt off on a monthly basis, the debt burden of credit cards on households will only continue to grow. To illustrate:

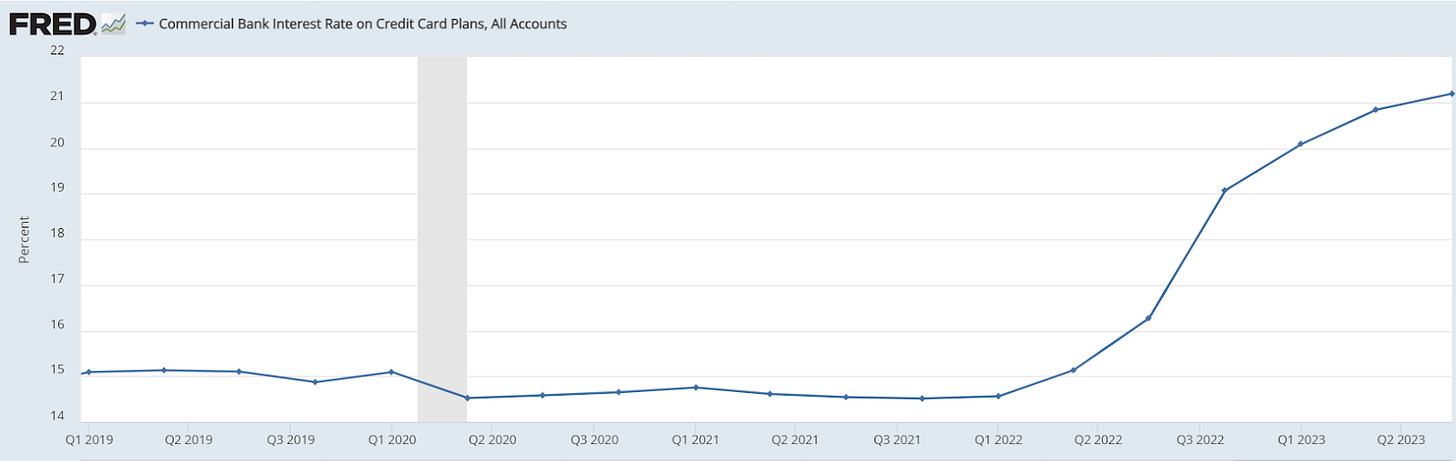

Furthermore, unlike mortgages, credit card rates are immediately impacted by higher interest rates - and liable to change based on the current climate. This is how consumers are taking a major hit from Federal Reserve interest rate hikes. Households pay more for something that has become a staple of the consumer experience in America - and they’re liable to pay even more as high interest rates continue to strain the economy. This is quickly becoming unmanageable to many: credit card delinquency rates are as high as they’ve been since 2011, and fast rising.

Factoring in Inflation and Wage-Growth

So the debt burden in the US is steadily growing, which is already alarming enough. But accounting for that, it is necessary to return to the initial problem of inflation, and to discuss the overall impact on the US consumer in light of wage-growth.

The labor market is - well, was - one of the positives of the post-Covid era: wages have been steadily on the rise since 2021, and wage growth has been outpacing inflation since February 2023. There were a number of factors that positively impacted the job market, including (but not limited to!) a tighter labor market with more demanding employees following the generous set of Covid stimulus checks, the impact of Keynesian-style stimulus spending allowing for corporations to expand their operations, and the massive set of renegotiations due to 2020’s enormous labor turnover.

The job market has proven resilient in the past few years, and though it is currently cooling, it remains reasonably strong - the cooling may in fact have contributed to greater stability by putting a cap on service-sector wage inflation of the sort we saw in 2022. It has proven to be a core driver of GDP growth (alongside productivity gains), contributing to the impression the US economy is doing much better than its peers.

However, this is not the whole picture. Let’s start by returning to wage growth versus inflation:

It’s true that wage-growth has been outpacing inflation since early 2023. But that was on the heels of 18 months of record inflation that did outpace wage growth. Income rose, but so did the cost of living. And the compounded effect of this is that the increase in prices will not be met by a commensurate increase in wages until Q4 of 2024. And this, it is important to note, is based on projections from September: before January’s unanticipated spike in inflation, and in the hope that the US maintains current labor market trends.

Furthermore, these calculations are also based on inflation and wage growth with all else being equal. All else is not equal: as mentioned above, credit cards exist, half of US households rely on them for basic amenities, and interest rates on credit cards have increased massively since 2019:

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

As a result, households can expect to spend additional funds on the interest for purchases made with their credit cards… for goods that have already increased in price due to inflation. The impact of inflation is thus compounded due to high interest rates.

This is the real reason why Americans are so dissatisfied with their financial prospects. The financial toll taken by the past few years on their lives and livelihoods cannot be adequately summed up by the more straightforward stories of wage growth, job creation, and the Federal Reserve’s battle against inflation. Behind all of the above looms a growing crisis of affordability and debt - one that can’t gainsaid by highlighting GDP growth or new stock market highs. With that in mind, it is simply not enough for interest rates to remain at the current level. In order to alleviate the debt pressure on Americans, they need to fall.

The Risks of Resilient Inflation

This situation is highly unstable. Economic prospects are dancing with debt on the edge of the abyss, and consumer sentiment shows that despite rosy projections, Americans are aware of this fact. There are several ways in which things might turn out poorly, but I’d like to discuss the most ironic one: resilient inflation.

US inflation numbers for December were a disappointment for many, as inflation was more persistent than expected, as were January’s. There is also an expectation that inflation will continue to hover above desired levels for February as well, though as of writing that remains up in the air.

The relative stickiness of inflation is partially due to its causes. As I’ve discussed before, and as has been debated by smarter analysts than me, inflation in the US was driven not just (and perhaps not even primarily) by an oversupply of liquidity, but also by supply chain disruption and bottlenecks caused by pandemic restriction and broader geopolitical upsets.

The effect that supply chain disruptions have on an economy are not all immediate: it takes a while for the impact of an issue to become fully apparent, and even longer for an issue to resolve into a price increase for consumers. As a result of this, there are still unresolved inflationary pressures working their way through the supply chain: namely, disruptions due to instability in the Red Sea and low water levels in the Panama Canal. Both of these have already had a tangible impact on their most immediate sectors - shipping costs - but have yet to play out for consumers.

The other issue with inflation related to supply chain disruption is that it is immune to manipulation via central bank policy. There is a wrench in the gears, a fly in the ointment: either it is resolved, or it isn’t, and will either way not be affected by the relative availability or scarcity of liquidity.

However, this has not prevented the Federal Reserve from treating inflation caused by supply chain disruption the same way it would inflation driven by money supply. It is unclear as to whether this worked. Yes, inflation has decreased, but given the nature of supply chain disruption, this was inevitable. Inflation caused by disruption is inherently transient - Federal Reserve action would therefore have been entirely superfluous to its natural resolution.

But because of the relative significance of purely monetary inflation due to US stimulus policy during the pandemic, which lends itself to a more monetary understanding of inflation in the US, it is entirely possible that the Federal Reserve overcorrected with its quantitative tightening. This is a problem, as it exacerbates all of the debt-related issues discussed above.

The potential catastrophe lies in the continued misidentification of supply chain inflation. As geopolitical issues continue to generate ongoing shocks to supply, inflation risks remain stubbornly high well beyond the next couple of months, reducing the likelihood that the Federal Reserve will decrease interest rates… which in turn increases the likelihood of triggering a recession.

How Likely is This Scenario?

This inflationary doom spiral remains a hypothetical scenario - a projection based on the existing circumstances. It is possible that the US economy will achieve its “soft landing” - immaculate disinflation with no recession (although American consumers will still have to contend with the overall increases in prices and the resultant drop in quality of life).

But frankly, I’m not optimistic. It is simply unreasonable to expect that a model of consumption entirely predicated on high levels of debt and low savings won’t react exceedingly negatively to historically high interest rates - something somewhere is guaranteed to break, and consumers will have to pay for it.

Shane McLorrain

Research Lead